ABOUT THE WRITER

Eric Kong Angal is a writer and worker raised in and currently living in the greater Seattle area. He his debut book, Defiler, a collection of short stories written between 2016 and 2025, is out now for you to download. You can find him on Twitter.

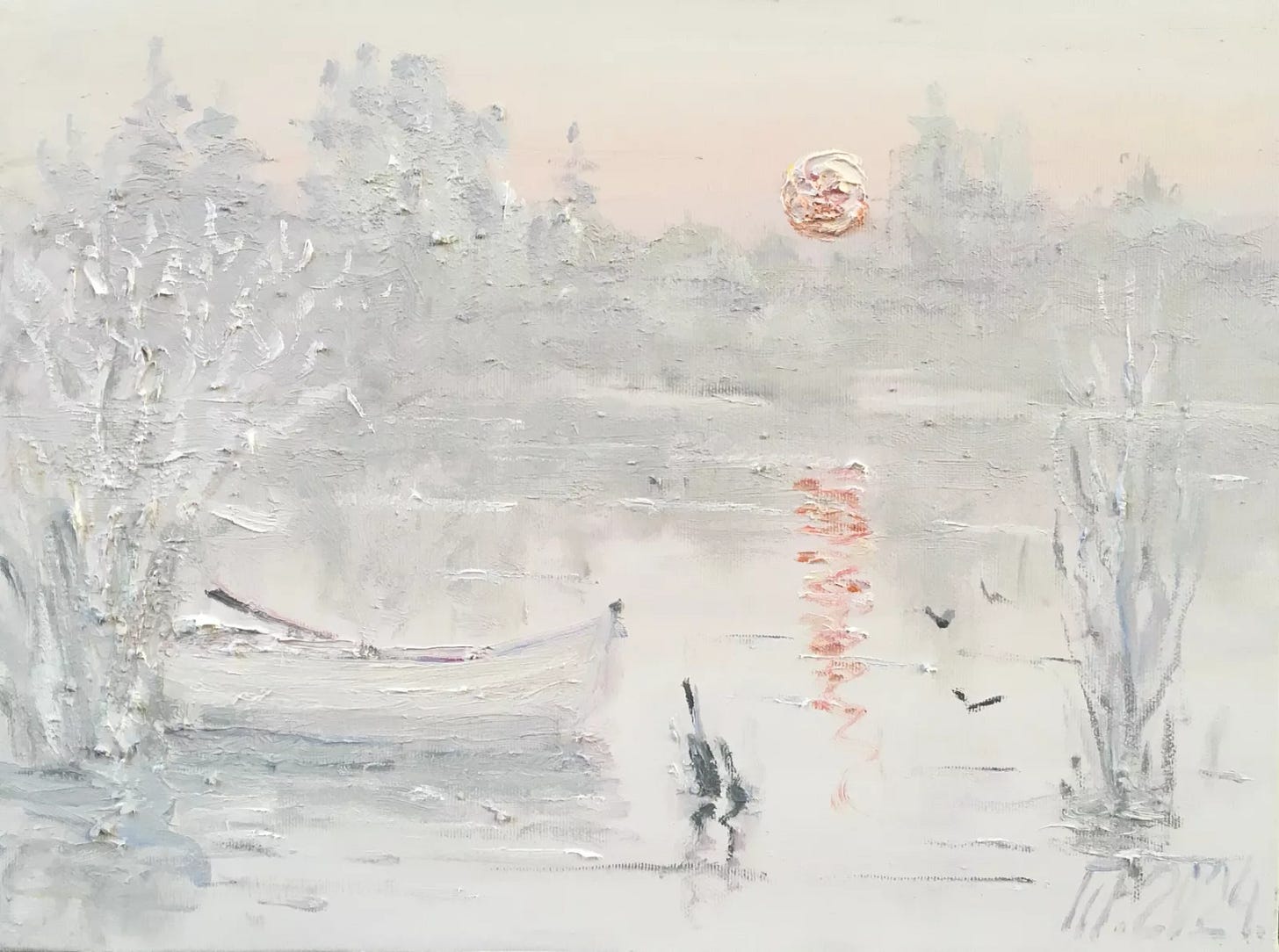

The morning is frost and a deep fog which obscures the lake, obscures everything.

An abandoned hutch bleeds mold. It is a forgotten artifact, a relic from a different time. Its paint is browned, ruined, gone, the wood unvarnished, the nails askew and all rust. The insides are spangled with cobwebs, bright with dew, strung up in the corners, in the dark, empty.

The water passes through the rocks and the runnel laps against the stone to form a rhythm, a susurrus in whose breadth you can individuate each drop. If you listen right.

The cold is only temporary. The fog will burn away, and the world will heat up all at once, but now is not that time.

The cars serried in their rows in the lot are all scabbed with frost, their windows occluded, and you can hear the seesaw sound of ice scrapers to punctuate a deep quiet. The dogs lead their owners in circuits through the lot, the new day exciting to them. They are connected to the morning’s sense of renewal, the dawn’s primordial beckon to life, unencumbered by the onus of quotidian languor, unlike their owners. For the dog each new day brings hope, in the relinquishment of shadows, in the paring of the earth’s great chill, and each morning soothes the hackles and unbares the teeth.

The coffee is poured into the mug with great ceremony. With its ingestion comes the purgation of those whispers of sleep which cling to you. Your stomach growls but you are not quite ready to eat. The energy to prepare a meal comes with time, and you are patient.

You ruminate on your dream. You dreamt of a world where a finger stretched across the earth’s rim, up in the heavens, an empyrean finger blue like the sky and shimmering like the moon in autumn, and as the earth curved so the finger became knuckled, and the finger came round the earth and back upon itself, and so formed a circle, or ring.

The little birds flit and flutter in apoplexy. They chirp their small songs and pass from branch to branch and leaf to leaf in keen animation. Each is an interlocutor in a conversation only they are capable of comprehending. Each burst of flight a shot from a gun, a communique whose meaning is veiled, an old secret. The larger birds are slow and they glide like wardens surveying the world beneath as it brightens before them. Their cries are long and high, as if to herald the death of the mist and the resumption of their great hunts.

The pool’s water is a translucent chartreuse, gelid and still. The maintenance guy was supposed to cover up the pool with a tarp and drain it some so as not to flood the poolgrounds, and they were supposed to run the pump to keep the pipes from freezing, but none of that happened, and so here it is. All that had grown in it during the neglect of its care now colors it this sickly green. The algae has died and the green still remains. The water does not brown nor turn opaque. How could this be, you think.

And what did you feel when you saw the finger? When you looked up into the sky to see the firmament split in two, bisected? You did not feel a fear, but a certain knowing.

The children leave their houses bundled in layers. Their limbs are made pillowy by their jackets, their heads dwarfed by their oversized wool caps, their faces flushed, eyes sharp in the cold. They huddle together within their parents’ orbit, waiting for the bus.

A rack of abandoned kayaks sits dormant aside a fallen pine. The pine was old and its roots were unshored and weak and the whole of it was felled by wind a few years back. Now it sits with its embrittled branches pointed skyward as if in opprobrium, its length seeming as if to revolt in quiet dignity: a slain colossus. The kayaks themselves are faded, bleached by sun and wind, their seaworthiness in question.

The coffee is sharp and too acidic but it must be drank bitter. For he who does not embitter himself in the morning may not muster the strength to face the coming day.

The low din of the ice-scrapers, of the birds, of the cars idling as they warm, all of this does nothing to punctuate the quiescence of the complex. It’s as if the whole world has held its breath to conceal something from you. Too early to think like this, too early to be mired in paranoia. A fetid report from the trashcan makes your nose wrinkle as you throw the old grounds in there–it’s time for the trash to be taken out. The sink’s teetering pile of dishes lurks sematic and predatory, the reflections of the ceramic like the glinting of teeth, the white of a roiled eye. And then another glint. In the far out, something else.

You walk closer to your window.

You dreamt of a finger suspended in heaven, some layer of heaven inaccessible to you, to anyone. You remember the public response was, frankly, apocalyptic. The people who were close to you were all scared, but none turned to you for help. They saw you as an equal victim whose power was naught. What the fuck could you have done about a finger in the sky, anyway. And what did it mean? They wept in fear of what was coming, wept for all they had not done, for all they had not gotten to see. A lifespan abbreviated by the presence of a disembodied finger which would, assumably, crush the Earth as a cinch would, or whose presence was a prefix to the arrival of some other horror, some other thing. But you were not afraid. You had not known it was a dream, but you were aware of something else. What was it, you think. You can’t remember now.

The water is mostly obscured by the fog, whose heavenly terminus has already been broached by the easterly sun, wreathing the land in long shadows. What has not been obscured is revealed to you as black glass. The lake is at the end of the complex and only a sliver of it is visible and what you can see is placid and still. You can smell now the neighbor’s cooking, the rich odor of bacon, the sweet undertow of pancakes. All of this makes the coffee taste worse than it did previously. Maybe it doesn’t have to be this dramatic, you think. Maybe some cream would be nice.

A single squirrel stands anchored to the trunk of a great cedar. You spot it parallel to your window, its tiny body pulsing as it breathes, its vacant eyes staring out around it as if considering something. It, too, is completely still, as if static. The honk of a distant car being locked or unlocked causes it to shoot upwards into the interminable mass of heavy foliage.

You remember now: the finger in question was yours. You did, actually, have access to it. What this meant or how that worked was unclear, but the finger responded to your every command. You could make the finger relax, straighten, and curl. You could raise or lower it in the sky. Its locomotion was completely divorced from that of your own corporeal fingers–some preternatural electrochemical signal could be transmitted to the skybound finger which made it move. There was no chance it would involuntarily do anything that was not within your power. This came as a great relief to you, and also, naturally, fomented a new line of questioning. A horrible realization had dawned: what if they figure out that the finger is mine? What would that even mean? Would you be killed? Or weaponized? And what would that mean for those you loved? You would probably never be able to see them again. And then the dream had lapsed, and you had awoken in a cold sweat. You understood none of it, but it didn’t matter anymore; it was a dream. Relief had washed over you–you took a deep breath. And then, miraculously, you had forgotten. But then something was still wrong. It was not a finger in the sky, the silence in the world, the dishes in the sink, the bitterness of the coffee, or the odor of the trash which had bothered you. It was something else. In your skin, your blood, a red note of dread. A burning realization of an error continually made. A remedial expiation to suffice, to steady your voice. You look out the window, you squint your eyes. Something shimmers in the very distance, just out of sight.