ABOUT THE WRITER

Alden Nagel is the founder and editor of Nut Hole Publishing. You can find him on Instagram. He has an upcoming novella entitled Salination Mountains, and a paired novel entitled The Desalinated Exosphere.

The Dekalog series of films, originally aired on Polish television in 1989, is the final of acclaimed and influential pessimist director Krystof Kieślowski. In consideration of The Dekalog, as well as that of his filmography as a totality, in consideration of the very first part of the filmic series.

Dekalog translates equivalently to “The Ten Commandments”, in which each episode takes for thematic inspiration. This inspiration is often considered tangentially loose, with the very commandments themselves not appearing at all directly in mention or in sight in the films themselves. The first episode in the series Dekalog: One is the most directly-thematically tied to the most real of religious themes themselves, featuring both Platonic dialogues about the existence of God, and the appearance of a scene that takes place inside an Eastern European-built church at the end of the episode itself (which does exist in Poland).

The entirety of the films are considered movies in and of themselves, only two others in the series were extended into true feature length films; episodes five and six. Titled in relation to their corresponding commandments; “A Short Film About Killing” (thou shalt not kill) and “A Short Film About Love” (thou shalt not commit adultery). The first episode, however, is often regarded as the most critically acclaimed, for its poignancy, and its tenderness in relationship to and with its subjects.

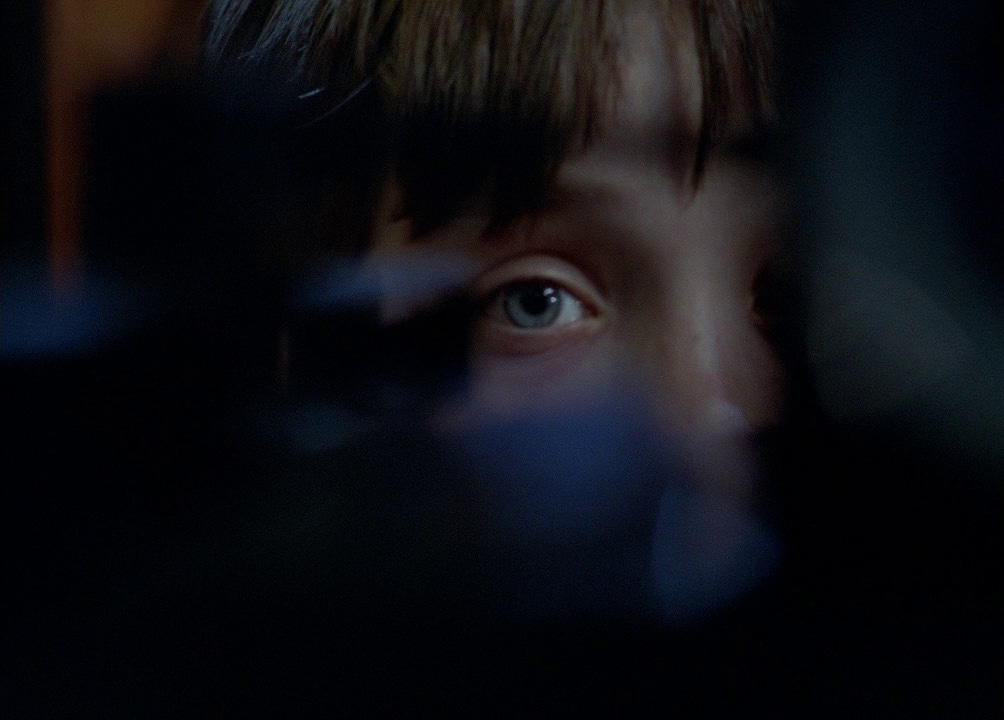

Attention is similarly due towards the film’s gorgeously enlightening writing and filmic direction. The visual symbolism throughout it is striking—allowing the film deeper, interconnected meanings that are worthy of repeated viewings and inspections. Dekalog: One begins with steady camera angles of an unnamed figure whose reappearances throughout the series of films stitch all the episodes together, whose significance may never be clear. These include that of a young man sitting beside a winter campfire, staring at the camera. The fact that he is placed first, and then paid almost no attention in the film’s remainder, entwines the everyday in a truly mysterious inscrutability. Who the audience is looking at, or “who is this person looking at us?” viewers may wonder. The unnamed man-figure appears to then wipe away a tear following a spatially-unrelated exposition of a woman weeping before a shop window television’s footage of a young boy whom we the audience shall learn to know his name: Pawel.

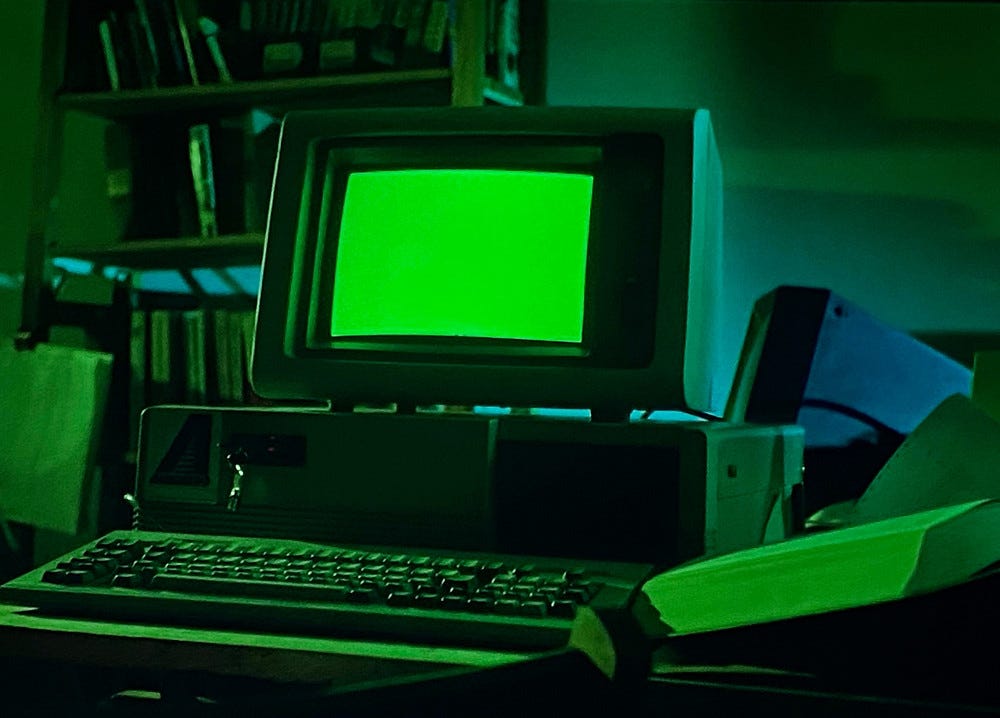

Moving carefully inside an apartment in the neighboring bloc, the scene’s camera then considers the boy and his father, Krystof. Pawel is excited about skates he knows he will receive for Christmas, and Krystof, having first confirmed the strength of the local pond’s ice (utilizing his mathematical knowledge, including localized information provided from the internet he has access to) as accessed on his apartment’s desktop computer, then agrees to allow Pawel to try his new pair of ice skates on early. He is a tender, sweet father to him.

Pawel is later seen participating enthusiastically and confidently in the scientific brainteasers posed by his university professor father, who specializes in relative and anthropological-linguistics and culture. Pawel’s own name is of note, too. In Polish, the name Pawel translates directly to tiny, humble, and also modest.

This reflexivity in the translation therein allows for the interpretation of the name depending on the analysis of it. Of course, this becomes most immediately relevant for Polish speakers. It also becomes immediately true for those who are tasked with providing subtitles for Dekalog. In an interesting understanding of its writing, the film approaches a modality of a form of perfection through its inherent subjectivity of temporal communication. The writing in the film, as well as in the other nine episodes, is precisely this accurate and pristine.

If there is a direct connection between this film and the first statement of the Ten Commandments (Thou shalt have no other gods before me) it may rest in science’s status as a kind of a metaphorical god for Kieślowski. His spirit is immediately humbled, if we are to project Krzysztof Kieślowski himself onto the child character. To presume otherwise is to project Kieślowski’s spirit onto any of the other characters within the show, including Pawel’s father. This reflexivity itself allows for an interpretive model which grants the presentation its strength. Dekalog: One’s generally solemn tone, of course, is not enough for a single viewing. A single viewing on its own (in my own view) is a captivating, decoratively profound and crater-powerful experience.

The incensed pride of placement which the computer occupies within the family’s home space may even extend the young man’s inscrutable watching a sort of youthful drive, which is sometimes ascribed to that of the divine. That very specific metaphorical and allegorical cathedral of phantom-beings which the film encapsulates offers a true resting space for the further tonal understanding of the late artist’s work in this hindering, boding directionality.

Pawel’s aunt, Irena, the woman seen weeping at the outset, however, is a Catholic who defines God as the love, and as made tangible in her embrace of Pawel. When Pawel is late returning from his English language tutoring lesson the next day, Kieślowski himself can be said to have felt an unease augmented by the nearby objects’ suddenly unpredictable behavior: a computer has switched itself on—an ink bottle falls and explodes to opaque shards. This could filmically-metaphysically explain the young Pawel’s death through a post-structuralist utilization of language.

The film’s linking language is further seen as a visual metaphor, assuaged to an unannounced discharge of hot water into a pond nearby, but the explanation’s omission in the film itself directs this away from more commonplace social criticism—and towards a true mystery without loud, unbridled thrilling suspense. In this sense, Kieślowski Kieslowski has made a religious film like none he has made before. He was known to be an atheist, a depressive, and a cynic that in full circumference both bearing and nearing the end of his own life would affably direct a film about that which can be said to be truly religious.

Krzysztof Kieślowski has through Dekalog: One defined that which is religious within it, by escaping what it appears to him not to be as a form of understanding—that which becomes transcendent by the truest passing of common, even banal beauties of worship and of ritualistic endeavor itself. The film dehumanizes and reappears as a proselytizing utilization of verisimilitude-based symbolism, and of an oft-compartmentalization-entranced reference to an entirety of life itself.

That very night, Kieślowski himself enters a church under a refinishing construction. He tips over a makeshift altar, whose candles then drip tear-like wax down the sculptured Maddona’s face. He does not see them: the camera holds on the side of his down-turned head as, with an appalling symbolic irony, he then presses frozen holy water against himself.

The last images are the juddering slow-motion frames of Pawel’s fade on the television seen at the start of the film, setting the tone for the whole series’ focus on that meeting point of transcendence and the everyday; the starkly true human face.

The depth of solitude in Krystof Kieslowski’s suffering is underlined by the absence now of any shot of anybody else weeping. The cold of being outside englobes the film, as it has Krystof, whose only other appearance will be in a wintry outside landscape in the episode Dekalog: Three.

The family’s computer coming alive and seeming to communicate directly with Pawel’s father Krystof can be seen as the wholesale intervention of the divine in the film, or rather, the infusion of the divine, and the mechanical. The computer displays the digital green text “I Am Ready” on its screen, without any human input to respond to, essentially creating its own sentience in real time, communicating a barren mystery.

There immediately questions posed to the viewership here. What is it ready for, exactly? What, if that is God speaking, is a God ready for? If it is for Krystof to submit himself to a God in response for his non-belief, punished unfairly in the form of Pawel’s death, then perhaps that gives us a semi-clear sign of an answer.

A newfound worry in our society, one that was not present at the time of Dekalog’s production but nevertheless is worthy of consideration is the hypothetical (yet very real) intertwining of A.I. and religion into an unbecoming entity analogous to desperation of some black cloud of unknowing mess. Some have speculated that this could come about by the inevitable worshiping of A.I. as it becomes intellectually and metaphysically superior to humankind. This would allow such a sensorial being to transgress its existence into a kind of God for the entirety humanity to worship unwillingly or not. Whether in the form of a disastrous A.I. creating new false godheads of spiritually-unspoken sociopolitical truth, or through the production of odd, horribly untrue religious movements.

In Dekalog One, the apartment’s home computer shown can be understood to be both a form of the wrath and the revelation of the divine itself. The technological has become an intermediary between Krystof’s uplifting of science as God in the form of objectivity itself. This real and keen idolization of science as a materialistic, universally ultimate truth (being one of the primary themes in the film) is in direct clash in the film with the theme of sanctity of God and worship of God—not science, A.I., or a complete objective truth behind the universe that Krystof proselytizes directly to his own son.

Milk (and other dairy products) are a frequent symbol in films and visual media for innocence—that which nourishes the young, and is reminiscent of an organism’s childhood. The milk spoiling in the film harkens to the loss of childhood wonder that Krystof instills in Pawel by promoting his idolization of objectivity and science, and a foreshadowing of Pawel’s eventual death. The nameless man seen at the beginning of the film must also be discussed. A homeless man, simply sitting in front of a fire by the very river that Pawel will eventually fall through and die in, says nothing, interacts with no one, and is merely a witness to the events of the film. However, he does break the fourth wall at the very beginning of the film, looking directly at us, the audience. Perhaps this could be said to be the human form of God, being witness to the events and activities of humanity.

These people are unwilling to intervene, thus letting the characters in the films, and perhaps in humanity as a whole, let their lives play out in chaotic, amoral, and even illogical ways. God itself is actively taking upon the form of a homeless man would similarly be a fitting candidate for our collective respect towards a God; indifferent and unkind, allowing God to be without love or recognition, simply existing untethered in relation to the daily lives of humans themselves. Poland in the 1980s was known to be a politically and emotionally fraught state in a perpetual form of chaos, the lives of those who lived within it to be deeply fraught and consistently affected by the oppression of the Cold War-era Soviet bloc to which Poland belonged, contemporaneously.

To fully understand the visual symbolism of the contents of the first episode of Dekalog, we must delve into the scene at the end of the film, which takes place inside a church. In this scene, Pawel’s father Krystof, in a fit of anger and wrath against a malevolent God, destroys the altar of the church. The church, being the Church Wniebostapienia Panskiego (translated in English to “Ascension Of The Lord”) in Warsaw, Poland.

The altar he knocks over is known as the Black Madonna of Csetochowa, an infamous local icon meant to signify the virgin Mary as shown through local tradition. Both venerated by Eastern Orthodox Christians and Catholics alike, the image shows the Virgin Mary holding up the infant Jesus Christ in her arms, positioned on her left side, with her right hands pointed towards Jesus, taking attention away from herself and positioning the Jesus Christ figure and the eventual salvation of mankind.

This position that she, the statuesque Madonna, is in is known as the Hodegetria position, which translates in a strict sense to “One Who Knows The Way”. In the process of knocking candles over that were on the alter in his anguished state, that were on the altar, he spills wax from the candles onto this icon, making the Virgin Mary appear to be as if she is crying, matching his rapturous tears in the wake of his son dying, similar to her crying at the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

It must be noted that the scene promptly ends with Krystof, while crying, emblematically sinks to his knees and tries to cross himself with holy water on his forehead, and yet the water itself remains frozen. This frozen water, of course, matches the very frozen water on the river that Pawel broke through while skating on earlier in the film.

This scene in the church ends with the character Krystof being truly vulnerable, helpless, and seeking for answers and guidance, even in the one place associated with what he had earlier in the film had sought to dissociate with, a church, the site of religious congregation and ritual. His understanding of death as an objective ceasing of all bodily functions is, in one sense, the literal answer to the meaning behind death in terms of how it happens. It does not provide him with the why it happens that he had been seeking out.

This certainly mirrors Pawel’s questioning of the nature of the universe earlier on in the film, when he encounters a dead dog, frozen on ground, on his walk in his neighborhood. What has initially caused him to become depressed and question the nature of things, leading him to ask his father for an explanation of why people and animals die, which is answered in turn by his father’s unbecoming answer of a cold, finite ceasing of the body’s functions—an answer that doesn’t assuage the young boy Pawel, or eventually that of his father at the end of the film following Pawel’s own tragic death.

Religion is as powerful as we believe it to have control over our lives. What I believe in terms of metaphysics does not matter; it has no bearing in any direct sense how I make my coffee, smoke my cigarettes, tie my shoes, take out the trash, or any other daily mundanity as it applies to all of our lives. Of course, this too is obvious to specify a singular person’s personhood. The very same applies to Pawel, his father, his aunt, and to everyone else presented to us within the Dekalog series of films.

To refer to the Dekalog series as a kind of a miniseries is itself an absolute, critical misnomer of titles and assigned meaning. Yet-both can be true. Queerly, it is also a matter of dialogical, positional and transparent belief.

I myself have a friend who is an ex-Mormon, and he once told me “religion never leaves a person”. I believe him, and I do not need to present neuropathological findings to prove his idea; it speaks only for itself. Kieślowski’s Dekalog films came to me during a time in my life I’d quip as especially godless. There is a very real power to these works, and a palpably sensorial experience which carries the full weight of an impermanence within.

To refer to Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Dekalog series as a kind of ode to Christianity is, in the weighing of it as a totality, is a full miscalculation. These films have a truly palpable and metaphysical force to them. Kieślowski’s Dekalog is my favorite piece of media and of film of all time, of course. As a collection, one of very few pieces of art I would call in full effect a craft of steered perfection of cinematic craft.

Dekalog: One is the strongest first episode of any episodic series I have ever witnessed. It may always be. No film, or episodic work of any kind, has ever expressed a further truth such as this; its timelessness will always exist with me, and move through me. No God or further Catholic metaphor can in a true void, express what a timeless piece of art itself can with its own height. Kieślowski’s film arrives at this experiential nature in full aesthetic-sobriety of cinematic being.

The English language is not enough on its own to describe the film’s transcendental energy; I am no expert on Polish culture or of the Polish language spoken within Kieślowski’s beautiful filmography. Polish as a language is a fine start to understanding this truth.

Dekalog: One is also a Christmas film. Many films for all people, for all times, which insist upon the regular, are themselves of none other. Christmas, as it appears within Dekalog: One utilizes time as mere setting—for it to be more would be nothing more as a totality of a whole of experience. In other words, it is a film about everything but Christmas, that happens to take place during those magical days of Christmas for the residents of the building within the Dekalog series.

One must believe, counterintuitively, that Dekalog: One is a film of pure love, of hope, of joy and of gratitude on the most purely existential plains of existence itself. There is nothing else one can presume safely with all due truth and applicable fervor. There is no truth to be found within Dekalog which it itself is not telling to us, the viewership, is all due and truth pathways. Dekalog transcends that which is the fictional, the experiential, the literal and the religious into something considerably greater. For this alone, it is a film of all-too true candor and a passion of absolute, totalizing, and even cataclysmically pure love.

Concerning the meaning of the Dekalog as a cyclical whole of films, Krzysztof Kieślowski stated the following:

Dekalog is an attempt to narrate ten stories about ten or twenty individuals, who—caught in a struggle precisely because of these and not other circumstances, circumstances which are fictitious but which could occur in every life—suddenly realize that they’re going round and round in circles, that they’re not achieving what they want. We’ve become too egotistical, too much in love with ourselves and our needs, and it’s as if everybody else has somehow disappeared into the background. We do a lot for our loved ones—supposedly—but when we look back over our day, we see that although we’ve done everything for them, we haven’t got the strength or time left to take them in our arms, simply to have a kind word for them or say something tender. We haven’t got any time left for feelings, and I think that’s where the real problem lies. Our time for passion, which is closely tied up with feelings. Our lives slip away, through our fingers.

You can view a great trailer for the Dekalog series here.